Cine-Machine as Method: Cine-Machines are optokinetic instruments

At this point of departure, I want to define a film machine as an optical-kinetic instrument used to create moving images. An example could be a film projector or a TV which converts a signal from respectively film reel and antenna. Both machines are optical in the sense that they do not create material objects, but only images of light, and they are kinetic in that they combine these images into an illusion of movement.

Contents

The kaleidoscope as a film machine

From the definition, a kaleidoscope can be considered a film machine, although it has traditionally been perceived as pre-cinematic. The kaleidoscope consists of an optical separation of the signal (the colored pieces behind the end of the tube) and the display that the viewer contemplates in the tube, as well as a kinetic union when patterns are transformed into other patterns as the user's hand rotates the tube.

If we are to identify the traces of the kaleidoscope in the imaging, it is easy to observe its inclinations. It is, on the one hand, an instrument that forms a seemingly infinite number of patterns with changing shapes and colors. We are astounded by its ability to create ever-new configurations, and without its images necessarily resembling reality, they suggest stars, flowers, Islamic ornaments, etc. At the same time, it's movement allows us to perceive each pattern in opposition to the solid reality from which we know the star, flower and ornament - the kaleidoscope is a window into a fluid reality where we can experience the coherence of these patterns in sliding transformations.

On the other hand, the actual, material mirror construction in the tube means that all the patterns follow the same basic shape with the same symmetrical necessarity. Its attractive ability to create an almost infinite series of pattern modulations is challenged by the fact that the kaleidoscope cannot form all patterns: it can only accommodate those which follow its symmetrical principle.

Thus, as a film machine, the kaleidoscope operates on some specific epistemological terms. It can, on the one hand, expand our world by allowing us to experience another fluid reality, where flower patterns are connected with star patterns. But at the same time, it also obscures reality, precisely because it's endless imagination is limited to the symmetrical configurations and sliding transformations.

Now let's assume that all film machines operate within this tension between expanding and obscuring our reality. The same assumption has been made about the mediality of the film, because each mediality also constitutes conditions that make them express reality in a certain way (cf. Elleström 2012). However, my criticism of this theory is that these conditions should be even more firm by anchoring the discussion in the concrete, material film machines, rather than an abstract and contingent idea such as "film mediality".

Material studies

When I make this claim to put material and machines into focus, this aligns with a broader "material turn" in contemporary art historical research. Among others, Ann-Sophie Lehmann has argued that a hylomorphic paradigm has dominated the Western world's understanding of art since the Renaissance. The paradigm originates from Aristotle, and in it lies both a dualist assumption that idea and material are separate categories, and a hierarchical assumption that the idea is more important than the material.

In art works, this means that works are perceived as "material manifestations of an immaterial idea" in the sense that "an ideal image of a form precedes the material appearance of that form in the physical world". In other words, the same idea and form can be transferred between different materials without substantially changing the meaning of the idea. Namely, the materials are "merely a carrier of meaning, but not meaningful in itself" (all Lehmann 2015: 22).

In contrast to the hylomorphic paradigm, "material studies" insist on seeing idea and material as a unity, e.g. by recognizing that materials can also be components of meaning (e.g., such as Monika Wagner's "material iconography" in Das Material der Kunst (2002)), or even that the materials can resist the idea and become an autonomous agent in creative practice.

In particular, the latter idea presupposes an intimacy with the material, which Lehmann believes has been neglected in academic discourse. Here, art is often de-materialized to reach a "higher" level of art theory that is detached from materiality. The knowledge of materials, on the other hand, is the subject for "non-academic spaces and activities (eg making, collecting and preserving art in the studio and the museum) " (ibid: 23)

But enough of the historical perspectives of materiality. What should interest us is the methodological problem of detecting the traces of agency in material. Lehmann believes that there is a historical tendency to reduce material issues to a causal relationship, often leading to technological determinism. To avoid this risk, she suggests James Gibson's concept of affordance as a possible foundation. The idea is that materials can afford a particular application or behavior, e.g. that buttons afford being pushed while handles afford being grabbed. There are always perceptual affordances where the actual action must always be performed by a human(?) agent, and thus not an indispensable causality. (ibid: 32)

In this way, the concept enables an openness that allows materials and tools to be understood in the creative practice among other factors, such as art-historical imitation, mimesis, etc. At the same time, the concept holds that specific materials promote particular forms of practice.

From material to substance

In comparison to the empirical data of traditional art history, film phenomena differ by using signals and machines rather than materials and tools. This relationship causes some terminological and methodological problems.

Therefore I would, first of all, like to clarify that the "material", whose agency I seek to prove in the works, should more precisely be called a "substance". In metaphysics, the term connotes both a causative substance (tilgrundliggende) of objects, as well as something "underlying" (underliggende) that we do not have direct access to. The substance (as a kind of Ding-an-sich) stands in opposition to the appearance of the object.

The material of a sculpture can be marble and a painting's material can be oil on canvas. Similarly, if we regard the material of the film, this must be light (and sound), because that is what makes the film sensible to us, whether this comes from a screen, a canvas, a kaleidoscope hole or something fourth.This needs clarification: Why is oil and marble not visually perceived too, thus being "of light"? The answer lies in the "optical" vs "plastic" nature of the medium. The TV with moving images is not a "material" in the same way as when light bounces of a sculpture or a painting to conceive a virtual space. Why? It's materiality consists of the display which causes changes in light that resemble motion, regardless of which underlying technology it uses.

But what we are seeking as an imprint in the cinematic artifact is something more underlying, which is actually closer to the traces of the tool in a piece of visual art (e.g. of a brush or a chisel). The film medium as an art form is based on modern technology and therefore dependent on different machines used in combination. We know that before the work appears on the display as a movie, it exists as a signal (a film reel, a VHS tape, a hard disk, etc.) that is produced, processed and transmitted by machines. Signals can be light particles, frames on an emulsion strip, an electrical signal or a binary code, but in any case, the final display phenomenon arises from an ecology of machines that create, translate, modify and display this signal.

Returning to the kaleidoscope, we can more easily imagine what is meant by a causative substance. We recognize it's symmetrical inclinations and given that there are only two components that can be varied - the glass pieces at the bottom and the angle of the mirrors - without any external sources (except ambient lightning conditions), it seems obvious to follow the appearing patterns in the monocle back to the mechanical structure. Although the range of patterns in the kaleidoscope is large, it is limited, because all of them are variations of the same basic form.

The monocle at the top of the kaleidoscope is a movie-like display where the user can see the graphical output of the mechanism. Here the position of the glass pieces determines an optical signal sent into the tube, while the pivot mirrors modify this signal by distorting it. We will label the pieces of glass as an input, where the signal originates, the mirrors that modify as a parameter, the hole at the top as the output and the unit of the input-parameter-output system as an algorithm. I will from now on draw diagrams of algorithms as follows:

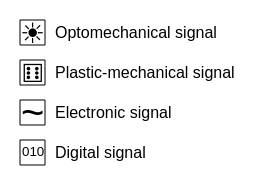

The box in the middle is the algorithm itself. Circles on the left are inputs, the arrows on the bottom are parameters, and the circles on the right are outputs. The small boxes on the arrows indicate the type of signal being sent. Here I use:

The algorithm metaphor states that if we know the values of input and parameter, we can predict what output this specific kaleidoscope will provide. Thus, the term can be used to generalize a film machine's graphical potentials (grafiske mulighedsrum) through abstract description. The algorithm is not itself a thing that appears in the film machine (or is filmable), but an abstract set of relationships that can be observed in the form of the realized appearances in a film. Thus, any pattern in the kaleidoscope will be a particular representation of the general algorithm of the kaleidoscope, and all outputs (patterns) can be interpreted as indexical imprints of a specific film machine's algorithm.

On the trail of imprints

Both the affordances and the algorithm will be used as concepts to detect the imprints of film machines to a cinematic artifact. However, it is not the interpretation but the detection of imprints that is the focus, and it is therefore important to distinguish this method from ex. material iconography, where the connotations of the materials are used for symbolic interpretationThis should refer back to the tradition described above., as well as from mere meta-cinematic effects, where film works refer to their materials, tools and creation process, in order to enforce the recipient's self-awareness and alienationThis should refer back to descriptions above, including "Materialist Film" by Gidal, Verfremdung in apparatus theory (ideology), and perhaps Kyndrup's "effects"..

The problem in these approaches is that they usually deal with signs that are conventionalized. In Peirce's typology of signs they are symbols, whereas the traces we seek are the direct indexical imprints of the film machine. In The Signature of All Things (2009), Agamben has linked Peirce's index with a broader idea-historical concept of the signature. To Agamben, the signature also appears in the art-historical context, for example when the art connoisseur Morelli closely studies paintings to determine if a work is authentic or a fraud:

"Instead of focusing attention [..] on more visible stylistic and iconographic characteristics, Morelli examined insignificant details like ear lobes, the shape of fingers and toes, and" even, horribly dictu ... such an unpleasant subject as fingernails. " where stylistic control loosens up in the execution of secondary details, the more individual and unconscious traits of the artist can abruptly emerge, traits that "escaped without his being aware of it.""(Agamben 2009: 69)

By turning the attention away from the subject matter and towards details, errors and noise, a connoisseur will see the imprints that are the signature of the individual artist and reveal a forgery. The same shift of focus away from the "motif" also occurs when Freud focuses on the slip of the tongue and traumas, as well as when the detail in deconstructivist analysis punctures the whole (ibid: 70).

The idea of the imprints in details, bugs and noise will also continue in this thesis. In Chapter 2, I will initially address the four environments to explore how the primary technologies of film mediality make their imprints. The chapter then raises the question of the validity of this method, because the conversion between film formats and the digital environment's integration of "analog glitch" filters have, in many aspects, undermined the security of the signature at a static level of signification. In comparison, the concept of the algorithm (as will be discussed in Chapter 3) can both maintain a relationship to the environments and use a more dynamic concept of signification that also incorporates motions, transformations and compositional principles.